Christian Pilgrimages

Christians have embraced pilgrimage as an essential search for stability in face of the ephemera of life. The practice can be seen in relationship to the religion's central tenet, the incarnation of Christ. Within a triune God, consisting of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the second person, the Son, is both God and Man through his birth from Mary. Consequently, both the search for the physical trace of God on earth and the desire to depict the person of Jesus have galvanized Christian piety from its origins. Since Christ's human nature died and rose from the dead, believers see a promise of the resurrection of the dead for all his followers.

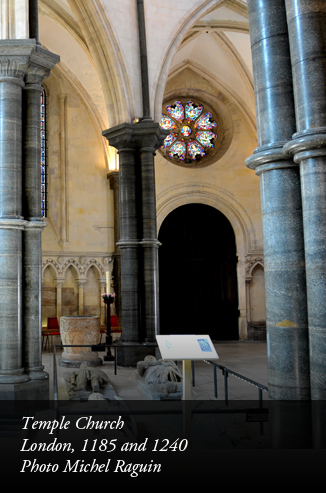

Since the earliest evidence of the cult, adherents expressed a desire to be close to the sites where the God/Man lived. The first object of pilgrimage was therefore the Holy Land, to places such as Bethlehem, (site of birth), the Sea of Galilee (site of preaching) and above all Jerusalem (site of death and resurrection). The anonymous pilgrim of Bordeaux wrote around 333 CE, arriving in the Jerusalem while the construction of the basilica of the church of the Holy Sepulcher was still in process. These early pilgrims were desirous of returning with a tangible souvenir of the pilgrimage. Relics for the pilgrim might be a stone from paths where Christ walked, water from a well, or even a piece of cloth or a statue that touched Christ's tomb. Later Christians far from these places often constructed replica sites, as did Buddhists who lived a great distance from India. Christians created replicas of varying exactitude of the Holy Sepulcher, such as the Temple Church in London, enabling those who could not journey to the Holy Land to revere in a special way the tangible moment of Christ's death and earthly resting place before his resurrection.

(continued)

Places of worship grew up over the sites of other holy graves, just as the grave of Christ was honored. At the same time that he constructed the great church in Jerusalem, the Emperor Constantine built the basilica of St. Peter over a cemetery believed to contain the grave of the first pope. The demand to be close to the tangible remains of heroic Christians, great confessors and martyrs, especially in the founding of new churches, encouraged the partition of bodies to allow the sacred "aura" that facilitated God's grace to be shared among a growing community. Churches were founded with relics as their essential talisman and stone altars with cavities inscribed with their list of relics dated from 320, a practice that was later routine. For the founding of Canterbury in the 5th-century, according to Bede (673-735), the pope provided Augustine with "all the things needful for the worship and service of the church, namely, sacred vessels, altar linen, church ornaments, priestly and clerical vestments, relics of the holy Apostles and martyrs and also many books" (Hist. Eccl., I, xxix). 08.

Pilgrimages continued as a vital aspect of Christianity through the centuries. The desire to honor a revered individual and to petition for special grace for oneself or for others provided the underlying reasons for the routine of pilgrimages. As Chaucer (d.1400) presented so vividly in the Canterbury Tales, when April comes with its good weather and sweet showers cause the bud to bloom, it simply follows:

Then do folk long to go on pilgrimage,

And palmers to go seeking out strange strands,

To distant shrines well known in sundry lands.

And specially from every shire's end

Of England they to Canterbury wend,

The holy blessed martyr there to seek

Who helped them when they lay so ill and weak (Prologue: lines 12-18).

It was the rhythm of life, a rhythm deeply imbedded into landscape, architecture, paths, buildings, statues, and images. Throughout the entire Middle Ages, and in Catholic Europe through the Renaissance and Baroque eras, the possession of relics of important saints made sites popular. Such indeed was Canterbury, with its body of a martyred archbishop who had challenged the authority of the English king. Veneration even included significant displacement to visit theses relics. The well-known autobiography of English pilgrim Margery Kempe (ca. 1373-1440s), who journeyed to numerous shrines, invariably associates them with relics, even locally, as at the tomb of St. William of Norwich.

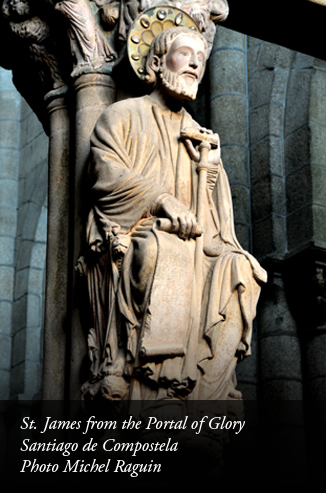

The tomb of the Apostle St. James the Great in Northern Spain was particularly important. Pilgrims walked hundreds of miles from Germany Switzerland and Northern France across the Pyrenees through northern Spain to reach the site honoring the man who lived and worked with Christ. Soon the image of the saint acquired the characteristics of a pilgrim to his own shrine, carrying a staff for walking, a broad-brimmed hat, long cloak, and the symbol of the pilgrimage, the scallop shell acquired from the sea a short distance from the shrine. The worshipper did not believe that the souls of the saints remained in such relics (body, bone fragment, or clothes worn), but that these things would act as conduits to grace. They would link the revered intercessor, the saint favored in the eyes of God, to his or her faithful on earth. Not only sacred viewing, at the core of Buddhist pilgrimage, but also alms-giving was essential to Christian practice. The last chapter of the 12th century Pilgrim's Guide to Santiago de Compostela discusses charity to be offered to travelling pilgrims.

(continued)

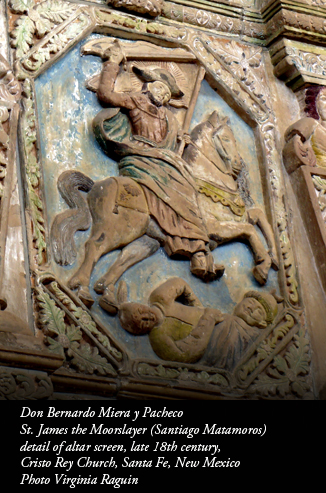

Commentators, however, not infrequently questioned the value and the validity of the pilgrimages. Santiago became a rallying cry for the "reconquest" of Spain by Christians and the saint developed into Santiago Matamoros: James the slayer of the Moors. What for one group may be a means of spiritual detachment and also charitable acts along the pilgrimage route could also become a focal point for xenophobic antagonism towards those who do not share the belief.

Christian pilgrimages are popular today. Holy cities like Jerusalem, with its places marking the death and resurrection of Christ are revered as sites sacred to the origin of the religion. The road to Santiago still attracts numerous individuals, young and old and from a diversity of nations. The motivations are diverse and include personal purification, experience of illness, and desire for bonding to a greater and more global community. Deeply personal needs are still expressed. In the New World, places like the Sanctuario of Chimayó in New Mexico bristle with petitions and thank offerings (ex votos) of baby shoes, portraits of children in the military service, or crutches and braces testifying to restored health.