Mulsim Pilgrimages

In the year 610 CE, when he was about forty, Muhammad, a citizen of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, had a vision which he experienced as a call from God to relay to his townsmen a message from God (called Allah). For twenty-two years he publicly proclaimed that message in what he called the Quran, "The Recitation." What God required was "submission" (islam), to a belief in a single God, This was troubling news for the great majority of Meccans who wanted no part in "The Submission" that was Islam. They got rid of their troublesome prophet, who found asylum in the oasis of Medina, but it was only a temporary respite. In the end, Muhammad returned in triumph: the Meccans became "submitters" (muslimun).

Every Muslim assumes a fivefold religious obligation. The first is a matter of faith, to pronounce and adhere to the conviction expressed in the Muslim creed, which begins with the rigorous statement of monotheism, "There is no god but the God," and ends with the specifically Muslim affirmation, "... and Muhammad is the Envoy of God." There follow four prescribed ritual acts: formal liturgical prayer five times daily; the payment of a annual alms; dawn-to-dusk fasting during the lunar month of Ramadan; and, finally, the performance, at least once in a lifetime, of the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca if physically and financially able.

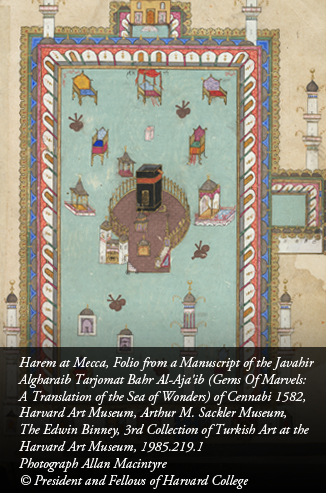

Muhammad identified an ancient structure held in reverence by the people of Mecca, a house believed to have been built by the Jewish patriarch Abraham (Ibrahim) and his son Ishmael (Ismael). Other religions, however, apparently had defiled the holy house (Ka'ba) meant to honor the one God with images that were idols of false gods. When Muhammad returned to Mecca, he cleansed the site of its idols.

(continued)

He kept, however, rituals associated with ancient practice. The first was the umra, the veneration of the Ka'ba and the second ritual was the Hajj, the journey from Mecca to Arafat and back in memory of Abraham.

(continued)

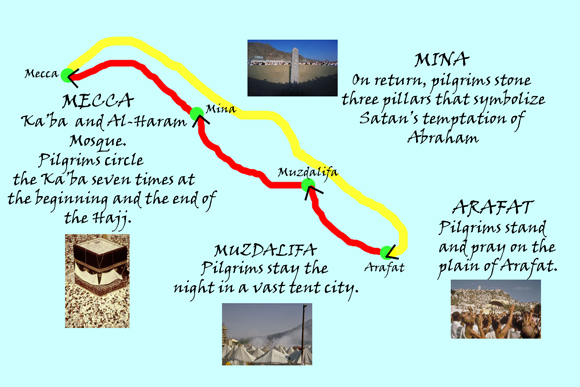

Upon entering Mecca pilgrims proceed to the sevenfold, counterclockwise circumambulation of the Ka'ba. They also attempt to kiss, touch or at least point to the Black Stone associated with Adam and Eve that is embedded in the eastern corner of the Ka'ba. The circuits of the Ka'ba completed, pilgrims go to the place called Safa, on the southeast side of the Haram, and complete seven "runnings" between that and another place, called Marwa, a distance altogether of somewhat less than two miles. The ritual commemorates Abraham's wife Hagar's desperate search for water for her son Ishmael. Today both hills, and the way between, are enclosed in an air-conditioned colonnade. The circuits of the Ka'ba originally formed part of the Meccan umra, but the empathetic running between Safa and Marwa was connected to it by Muhammad (Quran 2:153).

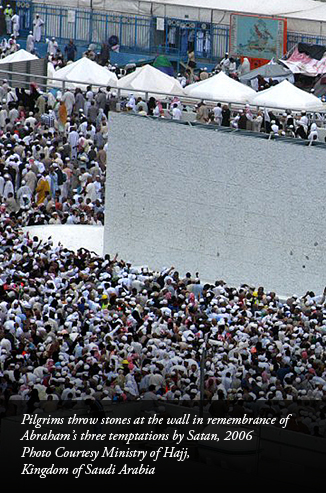

On the eighth of the month of Dhu al-Hijja, the Hajj proper begins. The pilgrims proceed to Mina, a village five miles east of Mecca, where most spend the night where they become, for that solitary evening, citizens of one of the largest cities in the Middle East. The next day, the ninth, is the heart of the Hajj. On the plain of Arafat that surrounds the tiny hill called the Mount of Mercy, pilgrims stand in white-garbed equality. At times sermons have been delivered during this interval, but the essential act is precisely the "standing before God," and examination of conscience from noon to sunset. Just before sunset there occurs the "dispersal," a rush to Muzdalifa, a place halfway back toward Mina. The night is spent there, and the next morning, the tenth, the pilgrims hasten to Mina for the "Stoning of Satan," the casting of seven pebbles at stone pillars. The ritual commemorates the belief that Abraham was tempted by Satan to resist God's order to sacrifice Ishmael; he banished the tempter by throwing stones. An animal is then sacrificed, commemorating Abraham's sacrifice of a ram, and the meat distributed to charity. The pilgrims then return to Mecca and again circumambulate the Ka'ba.

(continued)

The Hajj itself is profoundly personal and thus deeply transformative. A Muslim does not simply observe the liturgy of others, but performs himself, though in the company of other Muslims, an elaborate set of liturgical rites in which he is the sole and unique actor. Though he may be assisted through the intricacies of the complex ritual— Mecca has had from the beginning a guild of professional guides—his guides are only prompters; there are no intermediaries, no priests or clergy who mediate his actions to God. Like Abraham himself on that same terrain, he stands solitary before his God.

Although it is in no sense part of the Hajj, many pilgrims proceed to Medina to honor the Prophet's tomb before returning home. The practice of pious visits to shrines has long been a part of Muslim practice. Ibn Battuta was a legal scholar, born in Morocco, who traveled extensively across Northern Africa, the Middle East, India, and China. In 1325, at the age of twenty-one, he embarked on his first Hajj to Mecca. He passed through Medina before arriving at Mecca, leaving a moving reminiscence:

On the third day they alight outside the sanctified city [of al-Madina] the holy and illustrious. Taiba, the city of the Apostle of God (God bless and give him peace, exalt and ennoble him!) On the morning of the same day after sunset we entered the holy sanctuary and reached at length the illustrious mosque. We halted at the gate of peace to pay our respects. And prayed at the noble Garden between the tomb [of the Apostle] and the noble palm-trunk that whimpered for the Apostle of God (God bless him and give him peace) . . . We paid the meed of salutation to the lord of men, first and last, the intercessor for sinners and transgressors, the apostle-prophet of the tribe if Hashim from the Vale of Mecca, Muhammed (God bless and give him peace, exalt, and ennoble him).